Main Menu

Me with my daughter, Lily

This guest article is from Rachel Brittliff, Founder of Curious Kids’ Science. Her idea for the company, creating engaging and fun educational science kits and experiments, was born from her daughter, Lily’s, fascination with science. Rachel went down a similar path to us here at She Maps. Like us, she was dismayed by the studies showing that girls aged 6 believe that boys are better at science than they are. Or, the teenage girls who don’t think science is for them. And just like us, Rachel decided to do something about it.

Here, she shares how her own upbringing had a bearing on her career journey and how she approaches raising her daughter, Lily, with the knowledge she has now.

Rachel is one of our many inspirational speakers at EduDrone 2019. Don’t miss out on tickets to watch her in action, discussing how we can educate and change the future of our workforce.

Our attitudes as parents, carers and educators have a profound effect on the way that our children view the world and their ability to engage in education. While there are plenty of academic papers on this topic, I’d like to share my own story about how my mother’s love of books shaped the course of my high school studies and later my career opportunities.

I grew up in a house where reading was considered as fundamental to life as breathing.

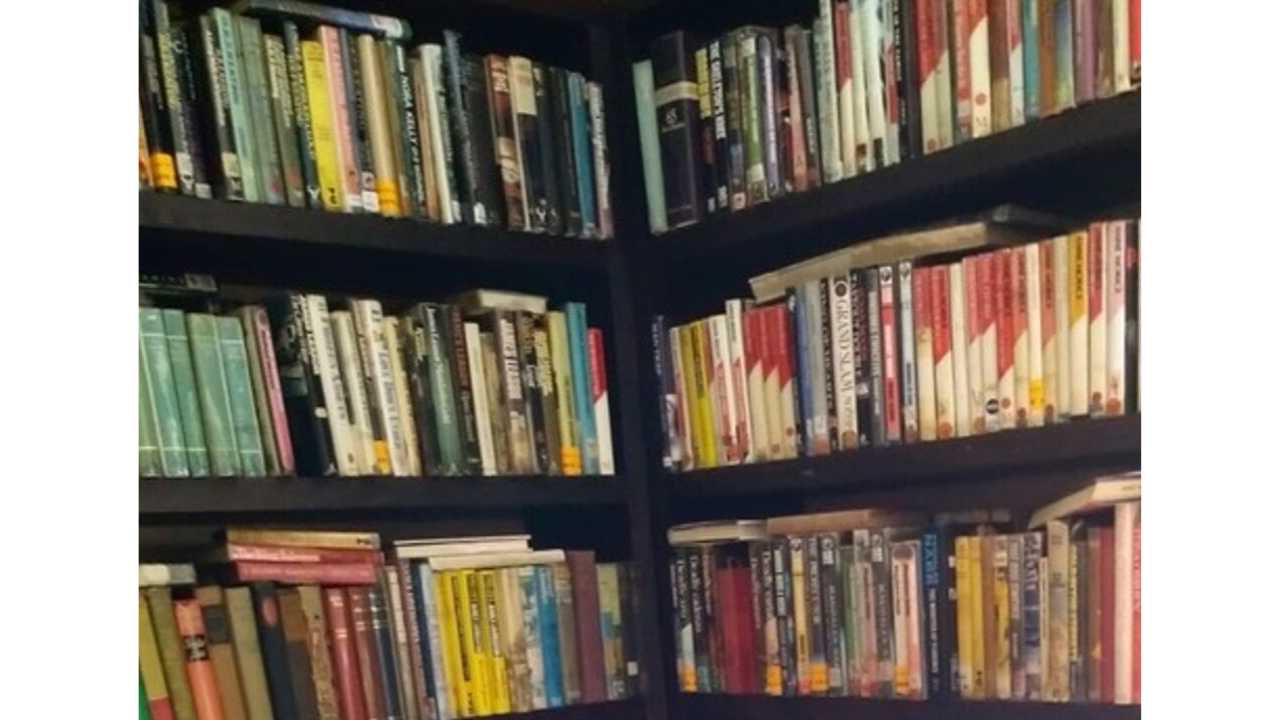

At our place, bookshelves lined the walls of almost every room. Discussions about books happened over dinner most nights and my mother prioritised reading well above cooking or cleaning. The standard answer to the question “when will dinner be ready?” was “ten minutes after I finish this chapter”.

I can honestly say that as I was growing up I came to view reading as being equal to breathing in terms of the necessities of life. It was definitely ahead of eating (at least by 10 minutes).

Both of my parents also loved history. My mother studied it at university and my father’s books were almost all history books of one kind or another.

It’s unlikely to come as a surprise when I tell you that in high school, I believed that I was talented in English and History. It honestly felt as though those two subjects were a fundamental part of who I was. In fact of the 12 units of study that I took for the HSC, 8 were English and History.

On the other hand, neither of my parents had any interest at all in science and my mother actually had a profound fear of maths.

I clearly remember my first science lesson at school. I didn’t have a clue what we were doing or why we were doing it. The language that was being used by the teacher was alien to me and I “knew” that science was never really going to be my thing.

Maths was slightly different. My father emphasised its importance and insisted that I make an effort to at least keep up. Dad insisted that while it might feel tedious, maths was a skill that would make my life easier and would result in my being more employable in the long run. So, I studied. I did better than pass the whole way through high school but maths was the subject that I dreaded more than any other.

I noticed a similar pattern of interest with my peers. In case after case, topics that were discussed at home became areas of excellence and interest at school. After I started to write this post I began to wonder whether there was any research on this phenomenon. The research that I found indicated that children were very likely to follow similar career paths or engage in study that was similar to that of their parents.

This used to be my childhood bedroom. When I left home, my parents converted it to a library where all four walls are totally covered in books.

If you think about it, I bet you can find a number of examples from your own circle of friends and family. It isn’t really surprising when you think about it though, is it?

I mean going back to my own experience, science was foreign to me. While I had mastered the difference between affect and effect by the age of 11, the difference between a conical flask and a beaker eluded me totally.

Fast forward about a decade and I had established myself in the workforce. As a Generation Xer I was possibly a little ahead of my time in that I found myself becoming bored of every job I worked in after about 12-18 months and searching around for the next challenge. My problem became that the workforce was not as segmented as school and university when it came to the skill sets required to effectively manage teams or projects. I discovered that I really needed to be able to estimate the return on investment for particular projects or model the revenue versus the cost of adding a person to my team. I also required skills that involved a consistent way to view problems, break them down into component parts and test solutions. In short I desperately needed to be able to do maths and science in the real world if I was going to be able to continue to change jobs and take on new and interesting challenges.

Although it was an uphill battle, I set my mind to improving my skills and am now competent at maths and fully understand how to isolate variables, but the experience taught me two valuable lessons.

The first lesson is that having the ability to learn new skills in a variety of areas is the key to not being trapped in jobs and roles that are boring or unsatisfying and the second is that the attitudes we have as parents about learning both positive and negative as well as our level of engagement in broad topic areas has a profound effect on the way that our children learn and the interests they develop.

Having researched, pondered and discussed these ideas over and over with friends, colleagues and educators I have come to the conclusion that the best way to help our children to learn the skills that they need for the future, is to engage with them on a broad range of topics, especially those that we aren’t necessarily comfortable with. In this way we can show them that it is okay not to have all the answers but that what is truly important is to keep looking for the right questions.

She Maps is Australia’s leading expert in drone and geospatial education.

She Maps assist schools with the purchasing of drones, school-industry created drone and geospatial teaching resources and highly supportive teacher professional development.

Ready to buy drones for your school? We are an authorised DJI reseller in Australia

Subscribe by email and never miss a blog post or announcement.

She Maps aims to bring much needed diversity and support to STEM. We do this by providing drone and geospatial programs to teachers and schools across the globe.

At She Maps we acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of Country throughout Australia and their connections to land, sea, and community. We pay our respect to their Elders past and present and extend that respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples today.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are advised that this site may contain names, voices, or images of people who have passed away.

Learn the 6 Steps to Launching a Successful Drone and Geospatial Program at your School

Take our resources for a spin and join the thousands of teachers who love our ready-to-teach classroom materials. Try one of our complete units of work for free.